Accommodation Insights

Travel Stories & Tips

Discover Turkey: Top Travel Spots and Tourist Attractions

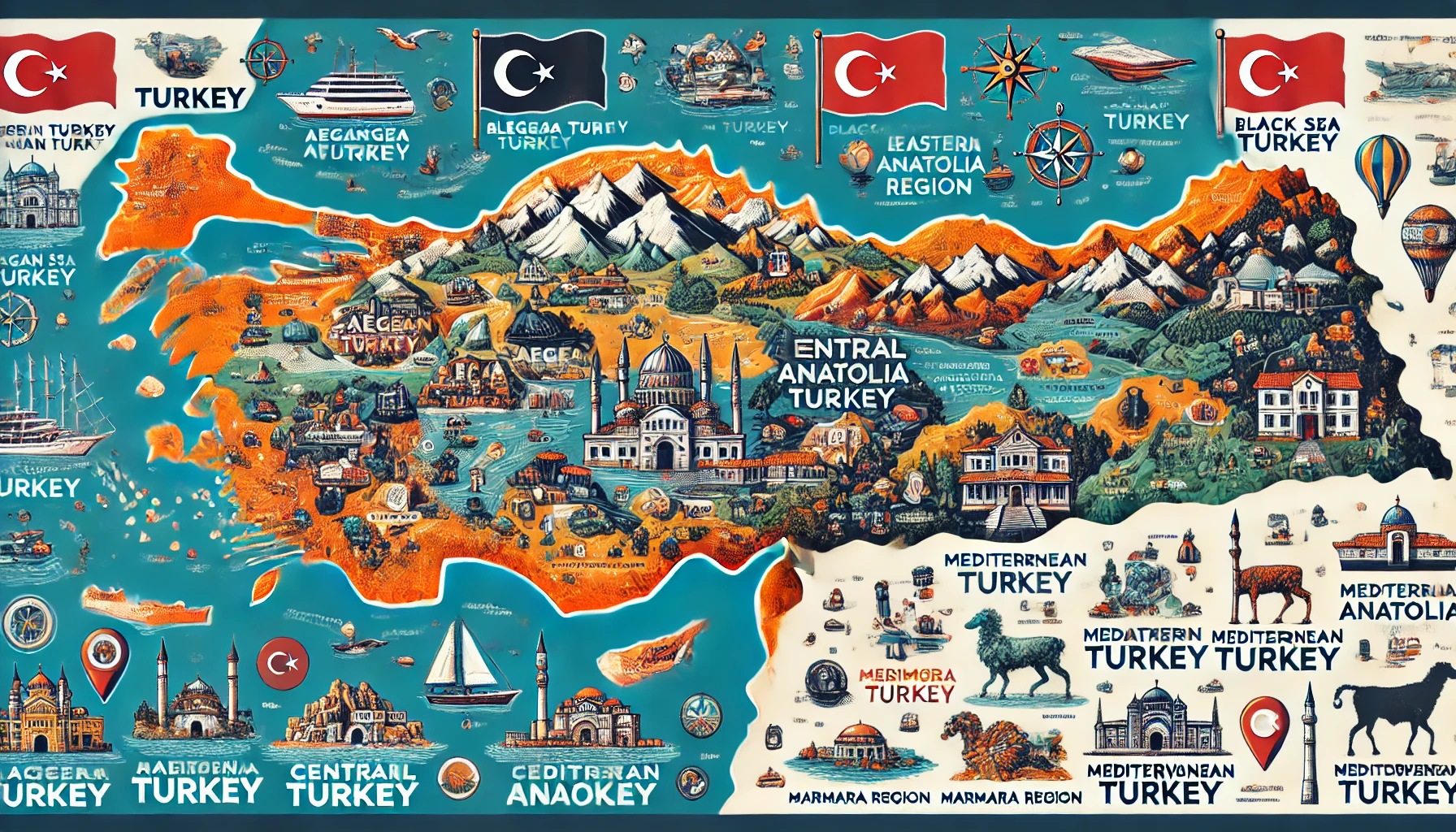

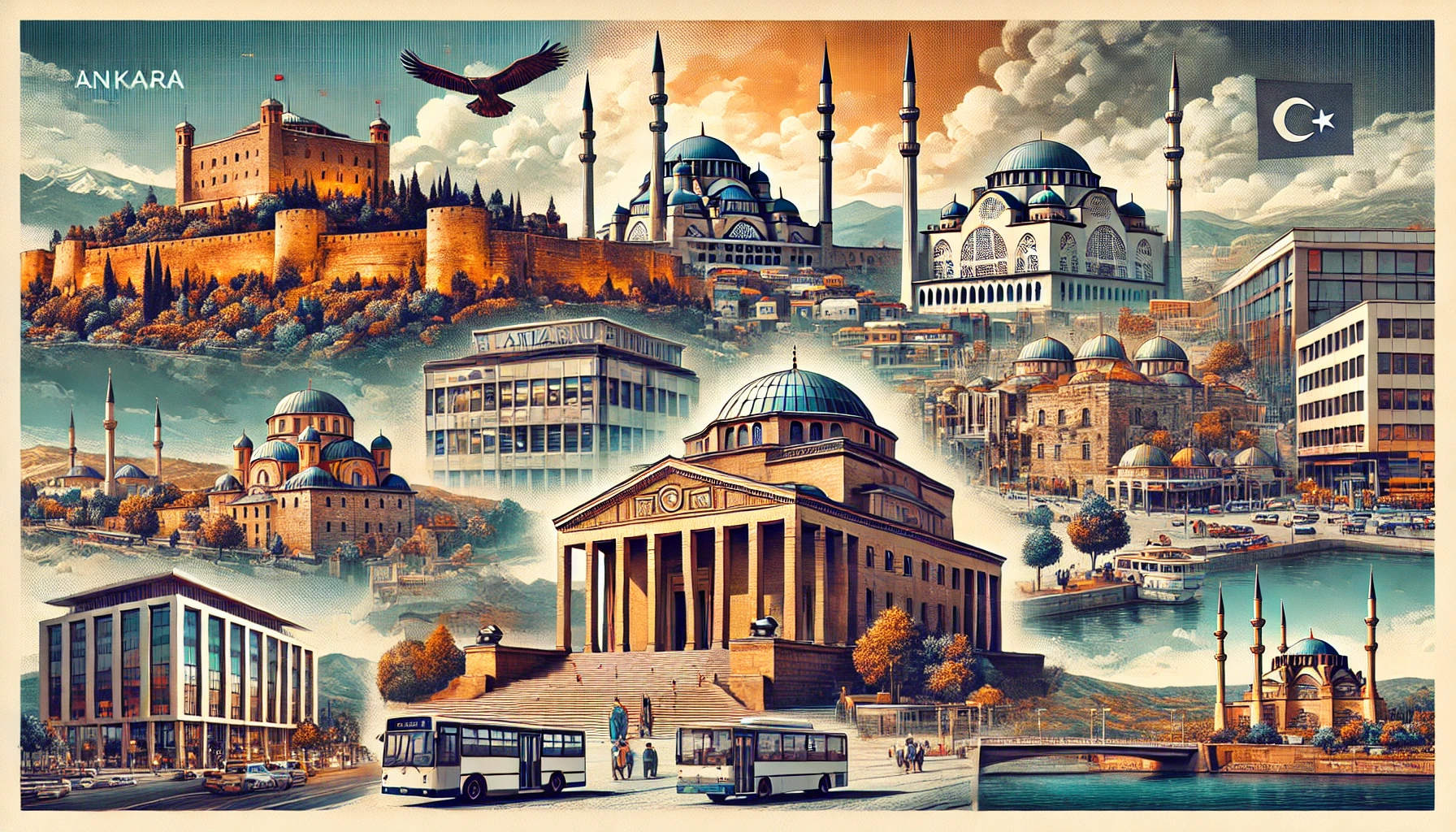

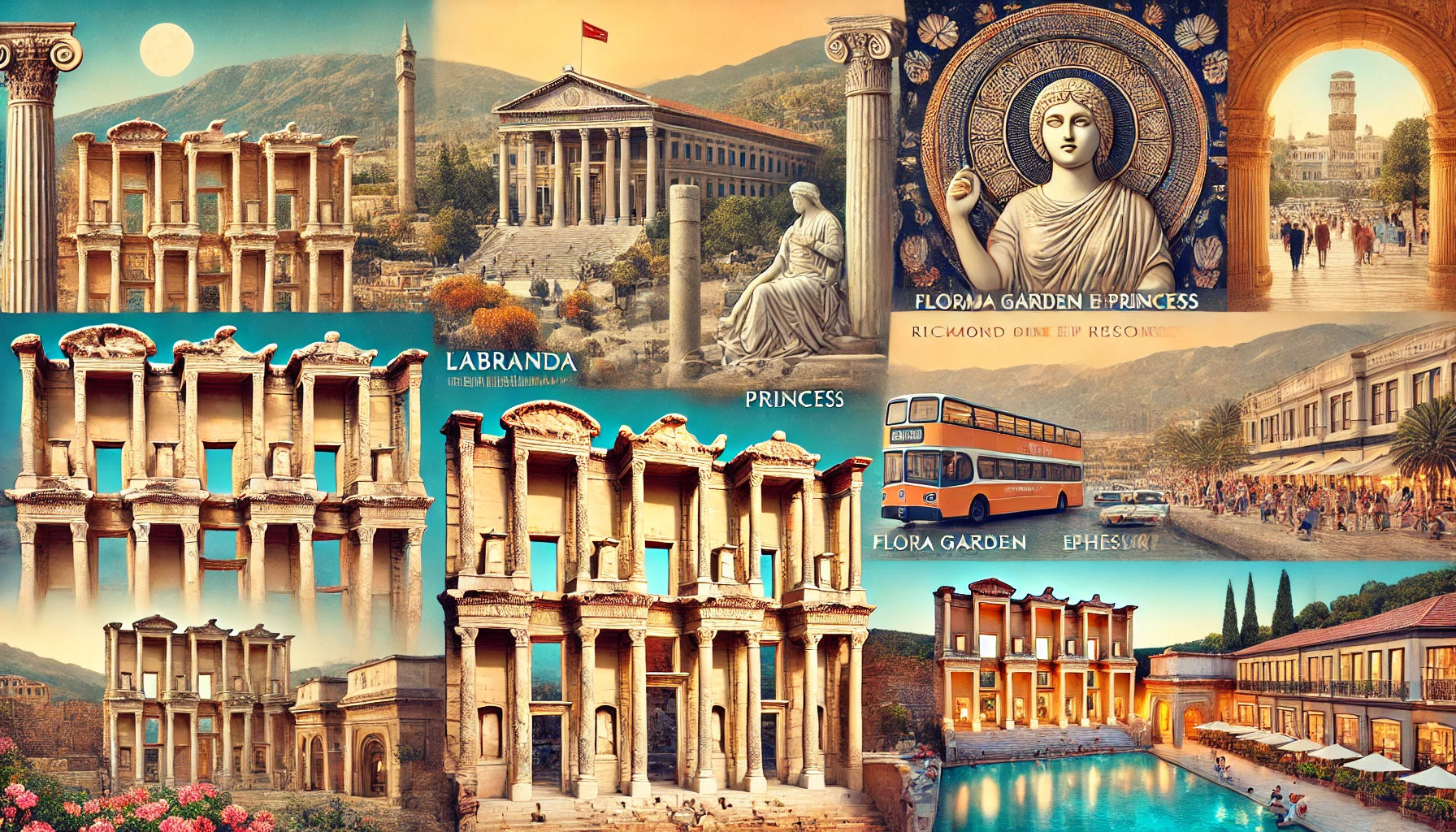

Turkey Travel Blog: Discover the best travel spots in Turkey with our comprehensive guide to must-visit destinations. Explore Turkey’s rich cultural heritage, stunning landscapes, and vibrant cities. From the ancient ruins of Ephesus to the breathtaking views of Cappadocia and the pristine beaches of Antalya, Turkey offers something for every traveler. Plan your perfect Turkish adventure today and uncover the top tourism highlights that make Turkey a world-renowned travel destination. Whether you’re seeking historical sites, natural wonders, or cultural experiences, our guide to Turkey’s must-visit travel spots has you covered.

When planning your Turkey travel, ensure you book your hotel and flights in advance to secure the best deals. Turkey’s tourism industry is well-developed, offering a range of accommodation options from luxury hotels to budget-friendly stays. Enjoy seamless travel with numerous flights connecting major cities like Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir. Embrace the warmth of Turkish hospitality and immerse yourself in the local culture.